Aviation is not an environmentally friendly form of transport, and airports have traditionally been regarded as zones of poor ecology. Yet, full-scale residential districts are now being developed around the world’s largest hubs, while the most progressive airports — seeking to reduce harmful emissions — are switching to renewable energy sources and exploring how to create a sustainable environment.

This article looks at whether an airport can ever be environmentally safe and how technology is evolving in this direction.

The airport as an urban ecosystem

Discussions about improving environmental conditions, saving resources, and implementing eco-technologies have long become part of mainstream urban development. However, in the case of airports, the idea of preserving a natural balance is rarely addressed. Most publications about airports focus on their negative environmental impact, while potential solutions are often overlooked.

Since aviation cannot realistically switch entirely to electric engines or biofuels — both technically and economically unfeasible in the near term — the topic of the “eco-airport” often remains unknown. Nevertheless, if we consider a large airport hub as a small city with its own “population”, housing, transport, administration, and community life, the need to preserve a healthy environment seems vital.

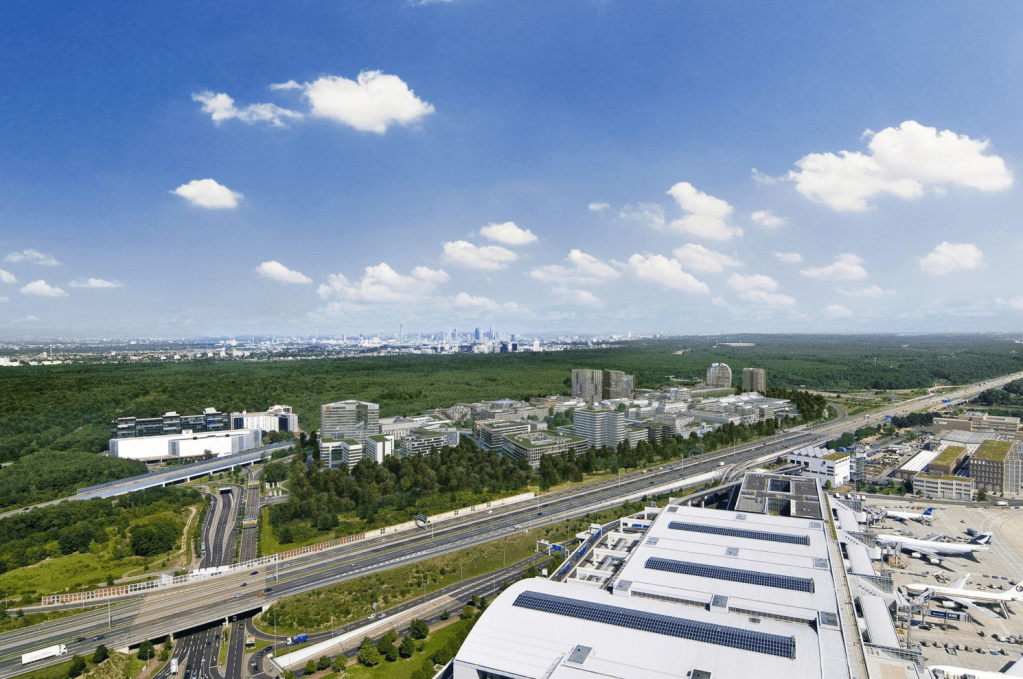

Fig. 1. View of the new Gateway Gardens district under construction at Frankfurt Airport. Source: aigner-immobilien.de

Urban-development practices such as the creation of public parks, construction of energy-efficient buildings, introduction of CO₂-emission limits, use of eco-friendly materials, and educational initiatives to raise environmental awareness all contribute to improving a city’s ecological situation.

Airports, however, are still perceived primarily as utilitarian structures — temporary spaces for passengers and essential infrastructure for economic growth. Yet the zone of influence of a major airport extends far beyond its physical boundaries: tens of thousands of people work there daily, many of whom live nearby with their families and spend free time in adjacent areas.

While regulations on noise levels, sanitary protection zones, and cleaner aircraft technology have improved, these measures alone are not enough to make a meaningful ecological difference.

Environmental impact and global emissions

The scale of global air transport continues to grow rapidly. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), the number of passengers carried by airlines worldwide increased from 1.6 billion in 2000 to 4.1 billion in 2017 and is expected to reach 7.8 billion by 2036.

Aviation accounts for around 2.5% of total global CO₂ emissions — a figure that may appear small but represents an enormous absolute volume when multiplied by billions of passengers. By comparison, if the global aviation industry were a country, it would rank among the top ten emitters of carbon dioxide in the world (where top 5 are close or >5%, and the rest are <3%).

Airports themselves are major consumers of energy and water — comparable to the needs of tens of thousands of households — and generates significant quantities of waste, not to mention the vast areas of land it occupies, often disrupting the migration routes of animals and birds. All these factors seem to argue against the development of airports, yet since air travel has long become an essential part of modern work and life, abandoning this mode of transport or drastically reducing mobility appears unrealistic.

For this reason, over the past decade, the need to monitor and reduce the environmental impact of airports has attracted growing global attention. Moreover, the experience of the world’s most progressive airports demonstrates that — with sufficient commitment — it is possible to achieve significant results in restoring the natural balance of their surrounding territories.

Fig. 2. Landscape park at Sacramento International Airport, USA. Source: vandertoolen.com

Airport Carbon Accreditation Program

In 2009, the Airports Council International (ACI) launched the Airport Carbon Accreditation Program, which assesses airports in terms of their environmental impact. Its goal is to reduce the negative effects of airports on the environment and move as many hubs as possible towards carbon neutrality — achieving a net-zero balance of CO₂ emissions. Participation is voluntary, but each year new airports join to improve their performance.

Within the program’s framework, emissions are divided into two categories: those controlled by the airport and those not controlled by the airport. The first depend on decisions made by the airport operator; the second arise from the activities of other parties — logistics companies, suppliers, or public transport operators.

For example, an airport authority can replace apron buses with biofuel-powered equivalents. By contrast, switching public transport buses to cleaner fuels requires coordination with external partners, dialogue with city authorities, incentives that encourage the use of low-emission transport, and similar collaborative steps.

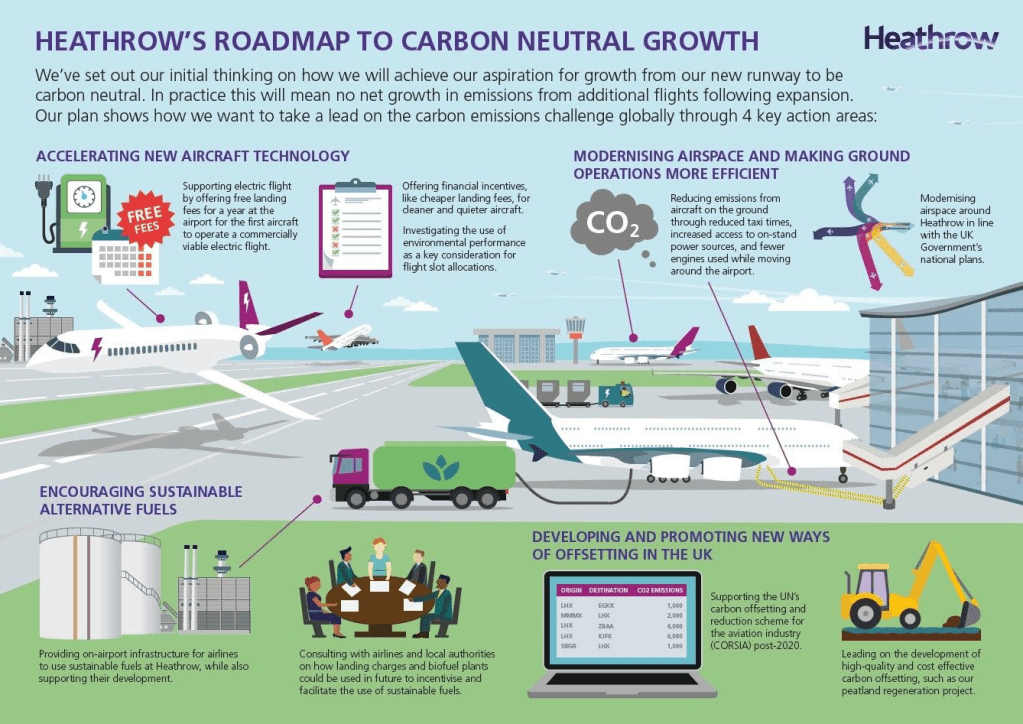

Fig. 3. Heathrow Airport’s plan for achieving carbon-neutral status, United Kingdom. Source: your.heathrow.com

In 2015, the member states of the United Nations adopted 17 global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for the period up to 2030, aimed at improving quality of life across economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Although these goals do not directly concern airports, they form the broader framework within which strategies for improving the environmental performance of transport infrastructure are being developed.

Later that same year, the Paris Climate Agreement was signed, and the international Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) was introduced — a system defining the mechanisms and requirements for offsetting and reducing the environmental impact of airports and the aviation industry.

Fig. 4. Sustainable Development Goals, United Nations. Source: un.org

There are several well-established international standards for the certification of buildings and structures in accordance with environmental and energy-efficiency requirements — such as LEED (USA), BREEAM (UK), and the German DGNB standard. New airport terminals may be built in compliance with one of these systems, depending on the country and the choice of designers.

In addition, there are ISO international standards covering environmental management (ISO 14001), energy management (ISO 50001), greenhouse gases (ISO 14064), and other parameters that define the quality and performance of materials and technologies. However, when it comes to airports, the Airport Carbon Accreditation Program remains the only system specifically focused on them.

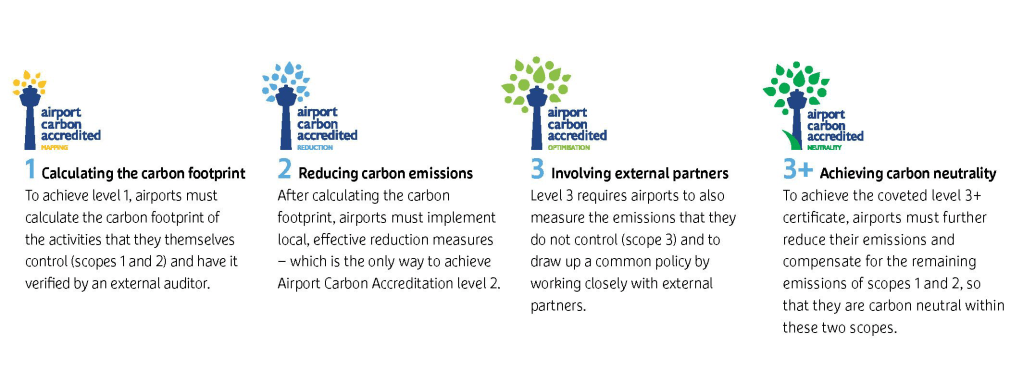

According to this program, the transition to carbon neutrality consists of four stages:

- Mapping – calculating direct CO₂ emissions.

- Reduction – improving infrastructure and reducing environmental impact.

- Optimization – accounting for emissions not directly controlled by the airport and developing strategies to reduce them.

- Neutrality – offsetting the remaining CO₂ emissions that could not be eliminated in earlier stages, thereby achieving a net-zero balance.

It is important to understand that an airport cannot eliminate all emissions. Therefore, the final stage of achieving neutrality involves offsetting — compensating for the residual CO₂ through investment in environmental projects at other airports or infrastructure facilities, in accordance with the mechanisms defined by the CORSIA program.

Fig. 5. Stages of airport emission reduction and control. Source: airportcarbonaccreditation.org

Airports’ carbon status

As of today, there are 49 airports worldwide that have achieved carbon-neutral status, of which 40 are located in Europe, including 15 in the Scandinavian countries — Norway, Sweden, and Finland. In the United States, there is currently only one carbon-neutral airport, located in Dallas. Latin America also has one — on the Galápagos Islands. In Africa, the only such airport is in Cape Town, while Australia’s Sunshine Coast Airport and Muscat Airport in Oman each represent their respective regions. The remaining four carbon-neutral airports are found in India.

At present, Russia does not have a single airport participating in the accreditation program. Moreover, due to political and bureaucratic reasons, the country is currently unable to join the CORSIA carbon offset scheme. Nevertheless, there are around 270 airports worldwide that have already begun to monitor, evaluate, and reduce their environmental impact. Importantly, these airports handle approximately 44% of global passenger traffic, and this proportion continues to increase every year.

The strategies and methods used to reduce emissions can be examined through specific case studies — both of major international hubs, where sustainable technologies provide long-term operational savings, and of smaller regional airports, which are often able to implement eco-friendly solutions more quickly.

The main sources of pollution at airports include aircraft during take-off, landing, taxiing, and ground handling operations, as well as airport service vehicles, public transport, and private cars bringing passengers from the city. There is also the issue of noise pollution, though thanks to the ongoing modernization of aircraft fleets, it has been significantly reduced.

A detailed list of all types of emissions can be found on the official website of the Airport Carbon Accreditation Program.

Case studies: Arlanda airport, Sweden

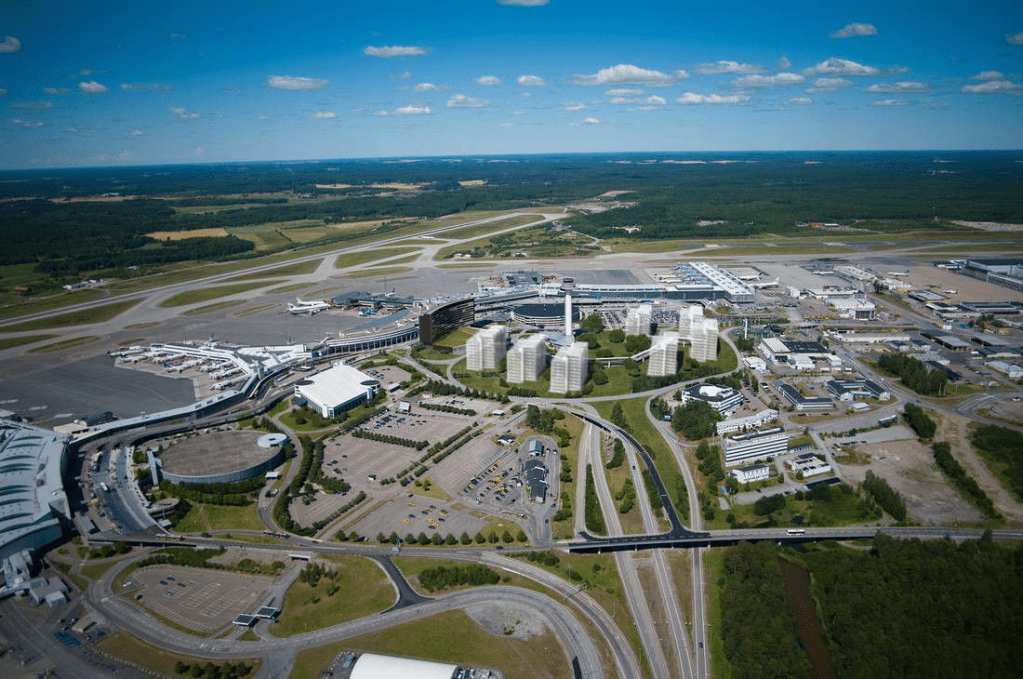

Fig. 6. View of Arlanda Airport, Sweden. Source: theflightreviews.com

The first international airport to achieve carbon-neutral status in 2009 was Stockholm Arlanda, which handles around 27 million passengers per year. Air pollution levels at the airport are comparable to those of a medium-sized city in Sweden — roughly 50,000 to 200,000 inhabitants.

Since 2005, Arlanda has succeeded in reducing its CO₂ emissions by 70%. Despite significant growth in air traffic over this period, emissions have not exceeded levels of 1990s. The airport’s heating system runs entirely on biofuel, and 100% of its electricity is generated from renewable sources. Gradually, the airport is also replacing its ground-service vehicles with biofuel-powered alternatives, even though their cost is several times higher.

The airport’s website provides detailed information on all implemented measures and its future plans for further reducing environmental impact.

Schiphol airport, Netherlands

Fig. 7. Airport Park at Schiphol Airport, Netherlands. Source: luxbeatmag.com

Another airport that has achieved carbon-neutral status and continues to actively improve its environmental performance is Amsterdam Schiphol. Since 2018, all the energy consumed by the airport has been generated entirely by wind farms. Given the scale of its consumption — around 200 million kilowatt-hours per year, equivalent to the electricity needs of 50,000 households — Schiphol has focused on optimizing how that energy is used.

To this end, a Thermal Energy Storage System (TESS) was installed for the terminal, four piers, and the airport hotel, reducing the need for gas in both heating and cooling. All airport lighting has been replaced with LED systems, and the airport operates the largest fleet in Europe of 100 emission-free buses.

In the long term, Schiphol is developing a strategy to adapt its existing infrastructure to meet the BREEAM-NL sustainability standard, while ensuring that all new buildings are constructed to achieve carbon-neutral performance.

Beyond the main hub, the Royal Schiphol Group also manages airports in Eindhoven, The Hague–Rotterdam, and Lelystad. Among them, Eindhoven Airport has already reached carbon neutrality, and the company plans to bring the remaining airports to the same level in the coming years.

Fig. 8. Noise protection park at Schiphol Airport, Netherlands. Source: aviation24.be

Airport holdings

The airports’ management by world holding groups has become one of the defining trends in modern aviation. So typically, when an operating company decides to join the Airport Carbon Accreditation program, this commitment extends to all airports within its network.

For example, the Manchester Airports Group, which operates Manchester, Stansted, and East Midlands airports, has achieved carbon-neutral status across all three. In Italy, the company Aeroporti di Roma manages both Fiumicino and Ciampino airports — each of which has also reached neutrality. Meanwhile, the French group VINCI Airports is one of the world’s largest operators, overseeing 46 airports that have joined the accreditation scheme. Among them, the airports of Lyon and London achieved carbon-neutral status in 2017, setting a strong example for the rest of the group.

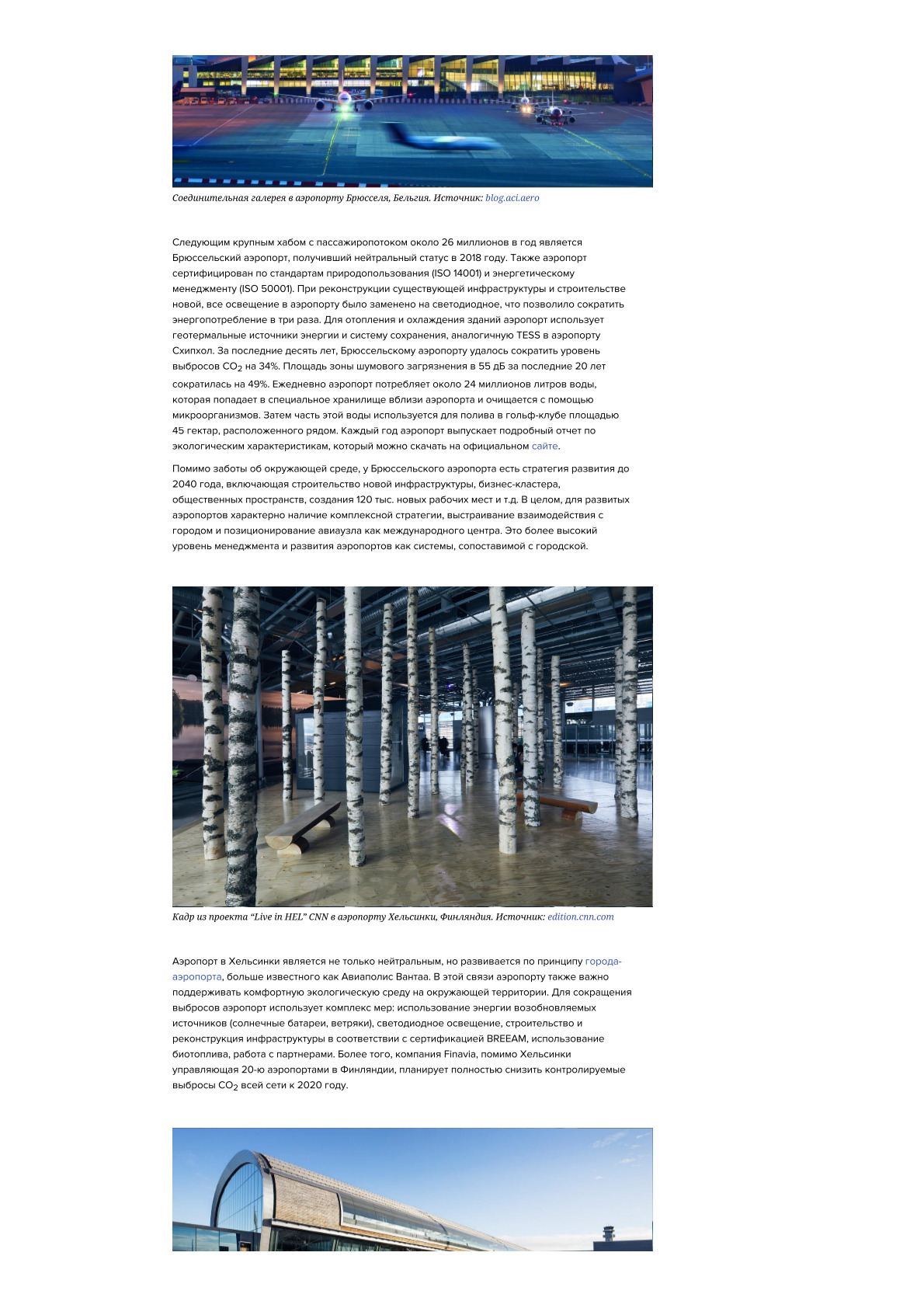

Fig. 9. Connecting gallery at Brussels Airport, Belgium. Source: blog.aci.aero

Brussels airport, Belgium

Another major hub — handling around 26 million passengers annually — is Brussels Airport, which achieved carbon-neutral status in 2018. The airport is also certified under the ISO 14001 environmental management and ISO 50001 energy management standards.

During the reconstruction of existing facilities and the construction of new ones, all airport lighting was replaced with LED systems, reducing energy consumption threefold. For heating and cooling, the airport employs geothermal energy sources and a thermal-energy storage system like the one used at Schiphol.

Over the past decade, Brussels Airport has succeeded in cutting CO₂ emissions by 34%, while the area affected by noise levels of 55 dB has been reduced by 49% compared with twenty years ago.

Each day, the airport consumes about 24 million liters of water, which is collected in a dedicated reservoir nearby and purified using microorganisms. Part of this treated water is then reused for irrigating a 45-hectare golf course located next to the airport.

Every year, the airport publishes a detailed environmental performance report, available on its official website. Beyond its ecological initiatives, Brussels Airport has also adopted a development strategy through 2040, which includes building new infrastructure, a business cluster, public spaces, and creating up to 120,000 new jobs.

In general, mature airports tend to adopt such comprehensive strategies, fostering strong cooperation with the city and positioning themselves as international centers. This reflects smart management and strategic development, where the airport operates as a sustainable urban entity.

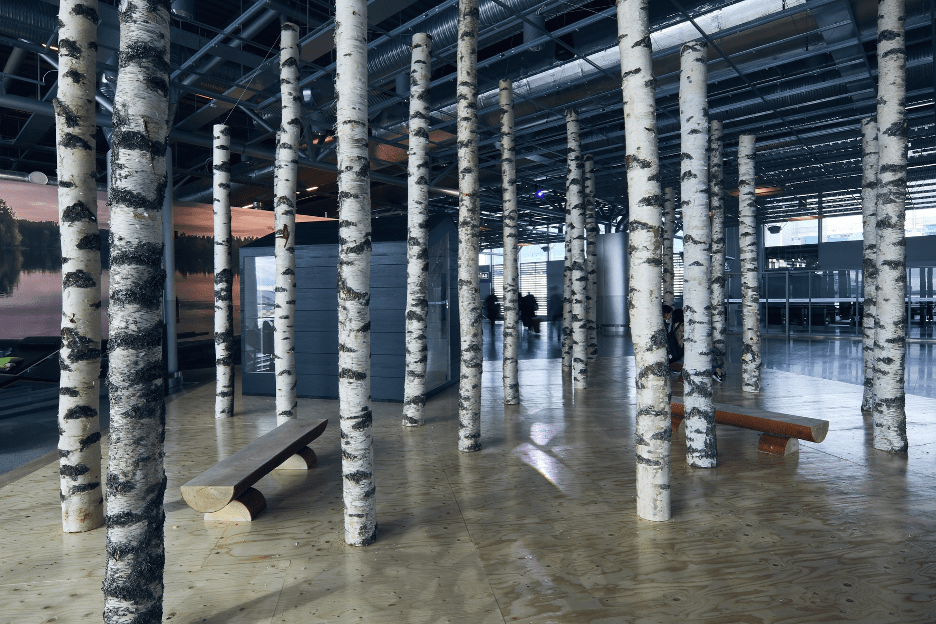

Fig. 9. Still from the “Live in HEL” project by CNN at Helsinki Airport, Finland. Source: edition.cnn.com

Helsinki airport, Finland

Helsinki Airport is not only carbon-neutral but is also developing according to the principles of an airport city, better known as Aviapolis Vantaa. In this context, maintaining a comfortable and sustainable environment in the surrounding area is equally important for the airport.

To reduce emissions, Helsinki Airport employs a comprehensive range of measures: the use of renewable energy sources such as solar panels and wind turbines, full replacement of lighting with LED systems, construction and renovation of facilities in accordance with BREEAM certification, adoption of biofuels, and active collaboration with partners.

Moreover, Finavia, the company that operates Helsinki airport as well as 20 other airports across Finland, has set a goal to eliminate controllable CO₂ emissions across its entire network by 2020.

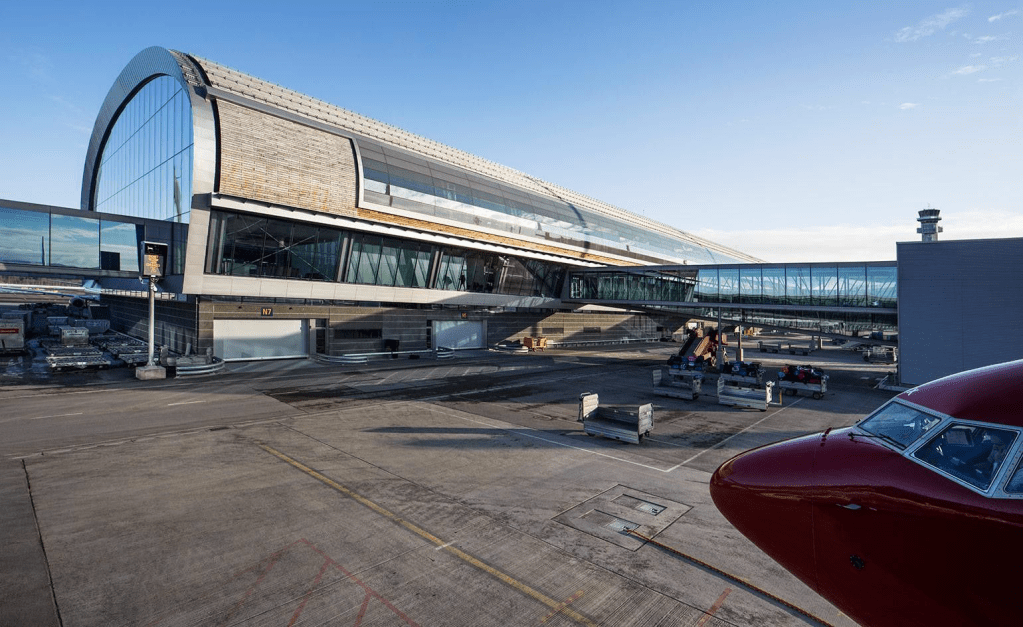

Fig. 10. New terminal at Oslo Airport, Norway. Source: wallpaper.com

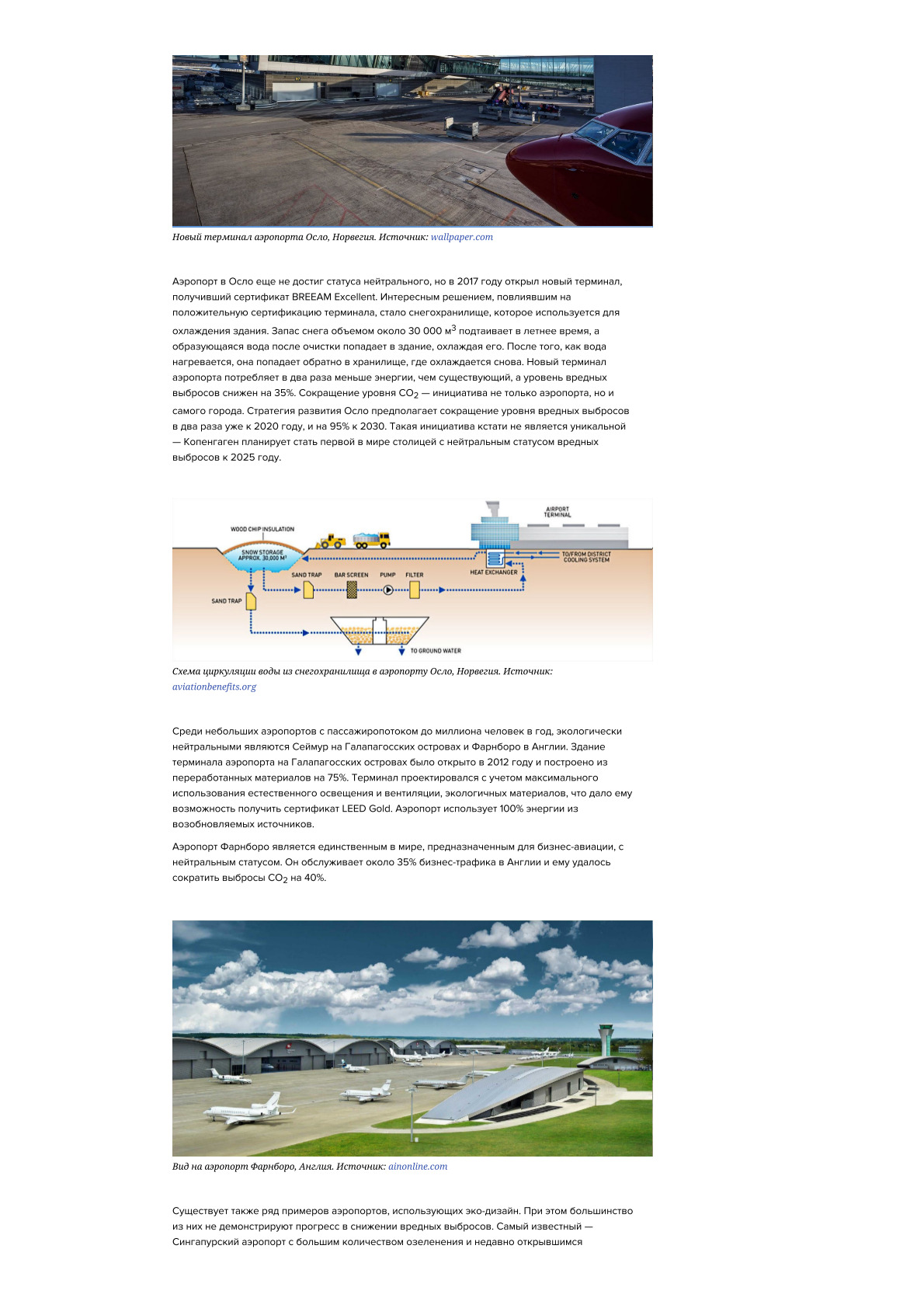

Oslo airport, Norway

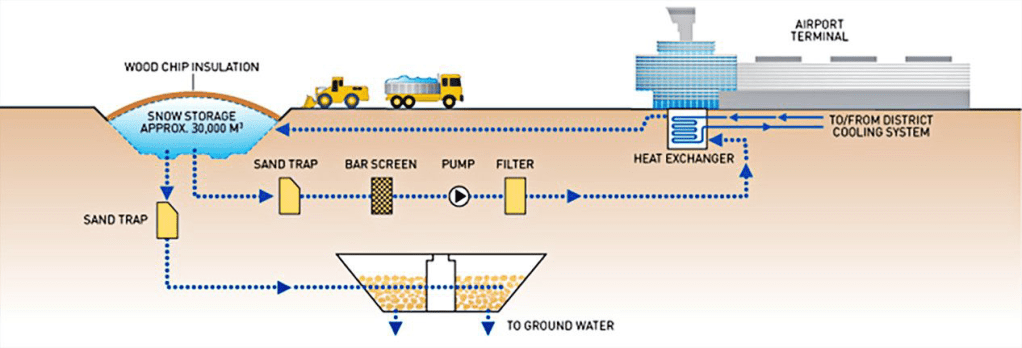

Oslo Airport has not yet achieved full carbon neutrality, but in 2017 it opened a new terminal that received BREEAM Excellent certification. One particularly innovative feature that contributed to this rating is the airport’s snow storage system, which is used to cool the building.

Each winter, around 30,000 cubic meters of snow are collected and stored. As it melts during summer, the resulting water is filtered and circulated through the terminal’s cooling system. Once the water warms up, it is returned to the storage area, where it is naturally re-cooled, completing the cycle.

The new terminal consumes half as much energy as the previous one, while its CO₂ emissions have been reduced by 35%. Emission reduction is a priority not only for the airport but also for the City of Oslo, whose development strategy aims to halve harmful emissions by 2020 and reduce them by 95% by 2030. This initiative is not unique: Copenhagen has announced its ambition to become the world’s first carbon-neutral capital by 2025.

Fig. 11. Diagram of the water circulation system from the snow storage facility at Oslo Airport, Norway. Source: aviationbenefits.org

Regional and business airports

Among smaller airports handling up to one million passengers per year, two have achieved carbon-neutral status — Seymour Airport in the Galápagos Islands and Farnborough Airport in the United Kingdom.

The Galápagos terminal, opened in 2012, was constructed using 75% recycled materials. It was designed to maximize natural light and ventilation, employing eco-friendly materials throughout — qualities that earned it a LEED Gold certification. The airport operates entirely on 100% renewable energy.

Farnborough Airport, meanwhile, is the only business aviation airport in the world to hold carbon-neutral status. Handling about 35% of the UK’s business aviation traffic, it has successfully reduced its CO₂ emissions by 40%.

Fig. 12. View of Farnborough Airport, United Kingdom. Source: ainonline.com

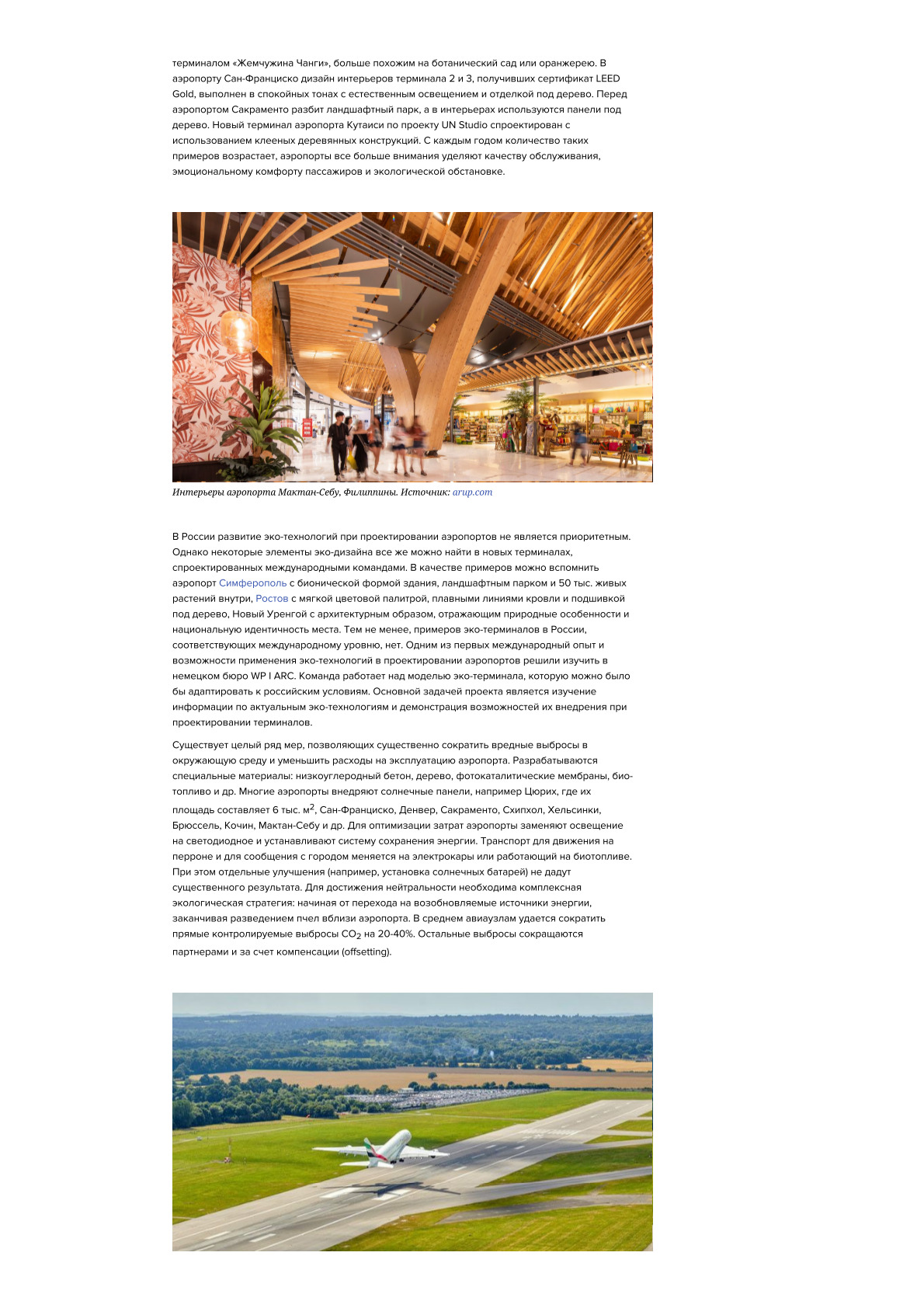

Eco-friendly design

There are also numerous examples of airports that incorporate eco-design principles, although many of them have yet to show measurable progress in reducing emissions.

The most famous example is Singapore Changi Airport, with its extensive greenery and the recently opened Jewel Changi Terminal, which resembles a botanical garden or conservatory more than a traditional airport.

At San Francisco International Airport, the interiors of Terminals 2 and 3, both LEED Gold-certified, feature natural lighting, muted tones, and wood-textured finishes that create a calm, welcoming atmosphere.

In front of Sacramento International Airport, a landscape park provides a green buffer, while the interior design continues the theme with wood-like panels.

The new terminal at Kutaisi Airport in Georgia, designed by UNS Studio, uses glulam timber structures, combining contemporary architecture with sustainable materials.

Each year, the number of such examples continues to grow. Airports are paying increasing attention to the quality of the passenger experience, emotional comfort, and the environmental quality of their spaces — confirming that ecological awareness is becoming a core element of airport design.

Fig. 13. Interiors of Mactan–Cebu Airport, Philippines. Source: arup.com

World developments

In Russia, the development of eco-technologies in airport design is not yet a priority. However, certain elements of eco-design can still be found in new terminals designed by international teams.

Examples include Simferopol Airport, with its bionic building form, landscape park, and over 50,000 live plants inside; Rostov Airport, distinguished by its soft color palette, curved rooflines, and wood-textured finishes; and Novy Urengoy, whose architectural concept reflects the region’s natural features and local identity. Nevertheless, there are still no fully eco-certified terminals in Russia that meet international standards.

One of the first to explore the application of eco-technologies in Russian airport design was the German bureau WP|ARC, whose team is currently developing a model of an eco-terminal that could be adapted to Russian conditions. The main goal of the project is to study current sustainable technologies and demonstrate their potential for integration into airport architecture.

There is a wide range of measures that can significantly reduce harmful emissions and lower operational costs. Special materials are being developed — such as low-carbon concrete, timber, photocatalytic membranes, and biofuels. Many airports have installed solar panels — including Zurich (with 6,000 m² of panels), San Francisco, Denver, Sacramento, Schiphol, Helsinki, Brussels, Cochin, and Mactan–Cebu.

To optimize energy use, airports are replacing lighting systems with LEDs and implementing thermal energy storage systems. Ground vehicles and shuttle transport are being replaced with electric or biofuel-powered alternatives. However, individual improvements, such as adding solar panels alone, cannot yield major results. Achieving carbon neutrality requires a comprehensive environmental strategy — ranging from the transition to renewable energy sources to biodiversity initiatives, such as keeping beehives near the airport.

On average, airports manage to reduce their directly controlled CO₂ emissions by 20–40%. The remaining emissions are reduced through partners’ efforts and offsetting programs.

Fig. 14. Gatwick Airport, United Kingdom. Source: internationalairportreview.com

As we can see, many airports — particularly in Europe — have begun implementing measures to restore ecological balance. The inability to completely transition to green transport does not make efforts to improve the situation meaningless; on the contrary, the successful experience of carbon reduction measures clearly demonstrates the value of such initiatives.

Since an airport is an integral part of the city, and in the case of a major hub, effectively creating an urban environment, it may be time to apply the same principles of sustainable development that we pursue in our cities.

The full text is published in TATLIN journal (in RUS).